Monday 24th April

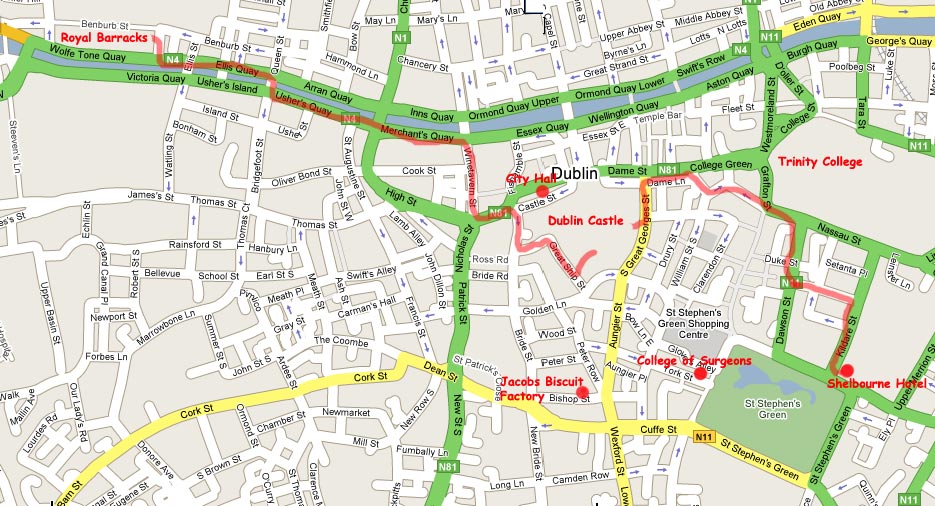

The rebellion started at noon on Monday 24th April. In Royal Barracks when the fighting started on Monday 24th April. The DMP phoned the Military HQ at Parkgate at 12.10 to say that the Castle was under attack by armed Sinn Feiners. Col Cowan then ordered men from Royal, Richmond and Portobello Barracks to march to the relief of the Castle.

Royal Barracks, now Collins Barracks, Dublin

The 10th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusilers were training at the Royal barracks on the Quays. My grandfather was serving as a Lieutenant with the 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and based at the Royal Barracks, on the day rebellion broke out. There were 37 officers and 430 men of 10th RDF in that barracks that day. The battalion was under orders to join the army in France. On Easter Monday he was detached to give a lecture to officers and men of his battalion on trench bombing and the use of explosives. At 11 a.m. they were assembled on the grass slopes of the barracks facing the River Liffey. Around noon rifle shots were heard from the city, and on hearing the bugle alarm call, he doubled the party into the barrack square. Here he found about 50 men of the regiment assembled with two staff officers and other senior offers of the regiment. Orders were given for troops to be equipped and armed. A party of men from A Company were marched out of the barracks. This is his tale from his own handwriting of what happened to B Company. I have also found the story of one of the Heuston men inside the Mendicity institute who fired on them.

I received orders to take B Company, about 50 men to the Castle. No further orders and there was no inkling that rebellion had broken out. I proceeded at the head of the party down a narrow street to the quays, where on turning a corner into Bridgeford Street, we received a volley of rifle shots which scattered our party.

"Easter Rebellion by Max Caulfield " has an account by Lucy Stokes, a VAD nurse on her way home. When she got to the Quays near the Royal Barracks she saw a large body of soldiers coming out of the Royal Barracks and taking cover behind the opposite wall of the Quay. An advance party of soldiers ran over the bridge with fixed bayonets, under fire from rebels in Guinness Brewery. Two officers politely suggested to her that she found a safer way home along the north bank of the Liffey. She saw the soldiers, whom she identified as 10th RDF edging their way cautiously towards along the quays. Although the advance party had crossed the river, the main party continued along the north bank, with the intention of crossing via a lower bridge, and making a direct assault up Parliament Street to the gates of the Castle. However they came under fire from the rebels in Mendicity Institue under John Heuston. The rebel fire scattered the soldiers. but they were able to leave a strong party to cover, from behind the Quay Wall, the rest of the RDF as they advanced. The main party continued toward Queen Street Bridge, which they crossed under heavy fire. At 1.40 the first military relief arrived at the Ship Street entrance, 180 men in total, 130 from RDF and 50 from Royal Irish Rifles

The officer following me, Lt Neilan, was killed, as were five or six men, and several more were wounded.

This is where this action took place. The Mendicity Instute is the building on the centre of this old photo.

The 10th Dubliners came along Aran Quay in the foreground then turned over the bridge.

Lieutenant Neilan, was officially reported as being shot by a sniper on Ushers Quay. Ironically his younger brother Anthony Neilan was taking part in the rising. Lieutenant Gerald Aloysius Neilan, 10th Battaliion Royal Dublin Fusiliers. KIA at the Mendicity Institution on Usher Island, Dublin. Aged 34. Son of John Neilan, of Ballygalda, Roscommon. Buried at Glasnevin Cemetery, Co. Dublin. Captain Stephen Gwynn of 6th Connaught Rangers, who was attached to 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, wrote in his book "The Last Years of John Redmond. Published 1919" When he asked the Fusiliers how their scouting worked during the conflict got the a\nswer "We needed no scouts, the old women told us everything". Gwynn then goes on to write "the first volley that a company of the 10th Dublins encountered killed an officer who was strongly Nationalist in his sympathies...others had been active leaders in the Howth gun running episode under Erskine Childers, and here they were in the British Army"

Official reports show two RDF officers killed that day Lt. G.A. Neilan and 2nd Lt G.R. Gray (4th Royal Dublin Fusiliers), with a further 5 RDF officers listed as wounded.

Casualty list of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers over the Easter Rising The following two men were killed on Monday 24tth April, but I do not know where and be certain as there appears to be no official record of their place of death. Heuston's Court Martial evidence from British officers says that 1 officer was killed and somewhere from 6 to 9 men wounded in this first skirnish.

In addtion to those killed during the Easter Rising there are wounded detailed in reports that mention 10th battalion men. There are other details of wounded, but they do not mention the battion of the RDFmen wounded

They had been fired on from the Mendicity Institute which was demolished in the early 1970’s. A book by P J Stephenson, the grandson of one of Heuston's garrison in the Mendicity Institute gives an account of the action from the Nationalist perspective. Heuston's garrison was initailly 15 men in total, and later received a small number of reinforcements. This is now the story from inside the Mendocity Institute.

"Heuston came into the room. He inspected the barricading of the windows, and then told us that the Irish Republic was to be proclaimed at 12 noon at the G.P.O., and that our job was to hold the Mendicity and engage any troops that would come out of the Royal Barracks across the river in Benburb Street until such time as the 1st Battalion, under Commandant Ned Daly, had taken over the Four Courts and had established itself there.... He ordered us back to our posts at the window and said: "When the troops move out of the Barracks wait until they are right opposite to you before opening fire. A single blast on my whistle will be the signal to fire". I turned the armchair with its back to the window, knelt in it and pushed my rifle out through the window using the top of the back of the chair as a rest and waited. The trams were still running along the North Quay across the river, and crowds of people of both sexes and all ages were clustered at the corners of Ellis's Street, Blackhall Street, John Street and Queen Street. Their faces were directed towards the Mendicity, nobody moved along the quays in front of the building. They were waiting for something to happen....

..... Reflection of this kind came suddenly to an end when my eye caught signs of movement across the Liffey on the quays. Incredible to relate the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Regiment were coming out of the Royal Barracks headed by an officer carrying a drawn sword in columns of fours with their rifles at the slope. The column erupted suddenly on the quay and continued to pour its khaki bulk out like a sausage coming from a machine. No advance guard - no scouts thrown out in advance to give warning of enemy forces lying in wait. Stepping smartly in time as if on a ceremonial parade the column came nearer to us, and to add to the air of festivity a tram came running along the tracks from the Park.

The Tommies had reached halfway between Ellis's Street and Blackhall Place, when possibly the strain becoming too much, someone downstairs fired. At that reaction of the rest of us was instantaneous, and we all let go. If Sean Heuston blew his whistle its sound was lost in the thundering reverberations that beat about our ears as the echo of the rifle explosions came back across the river from the houses opposite. I fired with the rest at nothing in particular, and suddenly became aware that I was pulling on a trigger and there was no recoil. I had emptied the magazine of the Lee Enfield in a wild unaimed burst of firing quite automatically and unconsciously. I filled the magazine again, put one in the breech and bringing my eyes into focus I saw that the tram was stopped, and had emptied itself of its passengers. The khaki column had scattered. Here and there in the doorways the soldiers crouched, some could be seen taking cover behind the river wall, others were making sudden jumps for the cover of the tram. The corners still had their clumps of curious and interested civilian onlookers.

The intermittent shooting from the Mendicity now sounded as if each shot had a purpose and a target. From where I lay in the window the rear platform of the tram showed a gap of daylight between it and the roadway and clearly underneath could be seen the boots of the soldiers coming from Ellis's Street in single file into the tram. Through the gap that lay between the rounded roof of the tram and the side could be seen the movement of the Tommy as he crawled along towards the front of the tram. It was just a matter of waiting until he was at full stretch to let one go. The crawling stopped simultaneously with the sound of the shot. While he was being dragged back at the top of the tram the boots under the platform offered a too inviting target and by the time the eyes focussed again on the gap at the top another victim was waiting and got it. Then the space under the front platform presented its sandy-coloured target and you let another go. For a long while this kind of grim triangular target practice went on without a single shot being fired back from the tram as it stood there mute and immobile. Then the sound of a whistle came across the river and the sandy coloured figures withdrew into the side streets, and silence beat down on your head and drummed in your ears. In those first short sharp minutes we had been made into soldiers. The first round was to us.

A check up revealed no casualties in the small garrison of 15 men. Murnane had gone out and could not get back, so he joined Daly in the Four Courts. The only damage so far were bullet holes in the back walls of the occupied room, and the window sashes....It was now very quiet outside the Mendicity, the curious foolhardy spectators were still on the corners; there was no traffic moving and not a sign of soldiers....Some time after he had gone a squad of Tommies without rifles or equipment, but carrying picks and shovels wheeled around the corner of Blackhall Place onto the quay heading for Queen Street Bridge. We immediately opened fire on them and they retreated on the double back into Blackhall Place out of sight. One or two of them staggered as if wounded. One fell on the corner and was dragged out of sight.

The next move against us came much later but this time from Queen Street. Moving out from the Barracks, possibly by Arbour Hill and Queen Street, the British were under cover of the houses until they reached the quay, and so were able to concentrate a large force in Queen Street without the slightest chance of our having a crack at them. We got the first sign of the new moves against us with a burst of fire from a concealed machine gun from the direction of Queen Street. We were down under the cover of the window sills in a flash, and for a while lay there stunned by the appalling din as the machine gun continued to rake the front of the building without ceasing. It seemed as if some giant steel whip was lashing the stone work with a tremendous vindictiveness.

Heuston shouted to us to hold our fire, but in truth all we could do was to lie watching the back walls of the room being riddled with bullet holes, and the plaster float around the room in a fine grey mist. He crawled across the landing and beckoned to me to come out. Crawling across the floor on my hands and knees I reached the landing outside safely. We collected a paint can bomb and a candle each, and getting down again on our hands and knees crawled into the long room near Queen Street. We took up our positions, one on each side of the third and fourth windows. The thickness of the walls and the bevelled sides of the windows gave us perfect cover and a slant-wise view of the outside was easily gained by keeping close to the window edge.

The giant steel whip was still lashing away, and under cover of the intense fire the Tommies began to rush across the high back of Queen Street Bridge. Heuston struck a match, lit his candle and stuck the long piece of the fuse of the bomb into the flame. He beckoned to me and I followed suit, and there we stood with the bombs under one arm with the fuse in the candle flame waiting for the rush through the front gates which we anticipated was to come. After what seemed like eternity the machine gun stopped firing, and I could then hear Heuston saying: "Don't throw it out until they are in the courtyard".

Looking out of the window I could see the round top of the helmet of the first Tommy, who, bent down under cover of the plinth, had come from Queen Street Bridge. When he came to the front gate he jumped across the opening like a rabbit and was gone towards Watling Street. After him came the rest of the attacking force in single file. How many of these rabbits hopped across that opening I could not tell. They seemed to be innumerable, and all the time the fuses of the bombs were in the candle flame, but no sign of them taking fire. At last there were no more hopping Tommies and incredible as it seems even now, nothing happened, and quietness settled down again on the area. The expected assault had not materialised.

At this time there were just l3 of us, as McLoughlin had not had time to return. If instead of hopping across the gate they had blown it open and rushed into the courtyard we would have been overwhelmed by weight of numbers alone. Amazed at our miraculous escape, I relieved myself of the weight of the bomb and returned to my post in the next room, thinking to myself, that if the bomb would not blow up it was at least heavy enough to knock a Tommy out if you got him in the right place.

There was nothing now to do except keep a look out, and listen to the sound of shooting in the distance; picking out the sharp wasp-like crack of the Lee Enfield and the deep boom of the Howth gun from the waves of sound rolling over the city and announcing to the world that for the seventh time in three hundred years the Irish people were asserting their right to national freedom and sovereignty in arms. The Tommies appeared to have gone back to the barracks, so we examined our rifles, cleaned them and pulled them through.....

As night had fallen by this time the city was in complete darkness, for the street lamps whether gas or electricity were not lighting. As the night wore on the houses opposite and the river disappeared into a black mass. The streets were silent and so were the guns. We talked quietly in undertones in the darkness, speculating on the possible course of events...

Meanwhile back with my grandfathers detachment of Royal Dublin Fusiliers

I re-assembled the party, leaving the injured on the road, and sent out an advance party of six men. The party proceeded across Aran Street Bridge and up Winetarven Street to James Street, along Christchurch Place in the direction of the Castle, The rifle firing in the adjoining neighbourhood had become intense from the South Dublin Union which was being subject to heavy attack. A few shots passed over us without any effect.

Ship St entrance to Dublin castle

I met Colonel M A Tighe of the Royal Irish Fusiliers making his way to the Royal barracks. He joined our party, and as senior officer took command. Passing Christchurch Cathedral a few revolver shots were fired. We entered a street running along the side walls of the approach to the entrance to the Lower Castle Yard. Here we came under heavy fire from rebels in the City Hall, which resulted in a further 20 wounded. The colonel decided that we should divide the rest of the party. He proceeded with his group down the long steps to the Ship Street entrance to the Castle. I took my group of about 10 men round by Ship Street Barracks, where we entered the Castle, having got them to open the gate for us and re-joined the rest of our original party.

On entering the Castle we found very few troops in occupation, and to best of my knowledge we were the only troops in control at that time. So we decided on placing sniper posts at various vantage points in order to curtail the sniping that we were receiving from houses overlooking the Castle. Sergeant Burke, who was an army schoolmaster, was killed when he and I were climbing a ladder to get up on to the roof to establish a point to deal with snipers. Burke was the finest type of man. He and I were great friends. He was a good soldier and it was sad that he should pass out in the way that he did.

25692 L/ Sergeant Frederick William Robert Burke 10th Battalion had enlisted in Gravesend, died 28 April 1916 age 21. Connolly and his small force had scaled the iron front gates of City Hall and installed themselves in the city hall. Connolly had previously been employed there in the Motor Taxation Office and would have been familiar with the layout of the building. On entering, he deployed half his men on the ground floor, proceeding himself with the remainder (including his brother Matthew) to the roof circling the huge dome. Shortly afterwards a troop of British soldiers arrived at the Ship Street barracks (this includes the 10th Dubs) and began to concentrate fire on City Hall. Snipers from surrounding high points began to pick off the rebels one by one and Connolly himself was reputedly shot around two o’ clock by a sniper operating from the Castle clock tower. According to some reports he slid down the roof after being shot and the Citizen Army medical officer, Dr Kathleen Lynn, tried to reach him on the parapet but was unable to do so.

The necessity arose of providing for the protection of the Castle in case of attack by the enemy in force. An SOS was sent out from Military Headquarters and at about 5 p.m. the Cavalry Brigade from the Curragh arrived, bringing with them food, ammunition and machine guns. Reinforcements from the regiments also arrived. And numbers of troops on leave in Dublin reported for duty. It then became possible to attack the strongholds of the rebels in the city. The first task was to clear the rebels out of the City Hall, which overlooked the Castle, and which they were using to fire on troops in the Castle. The City Hall was attacked by a determined effort by our troops. They were strongly resisted, but we managed to get them to surrender after hand to hand fighting. Casualties on both sides were high and many rebel prisoners were taken. A thought that came to my mind when I saw the amount of female clothing lying around was the possibility that were making a get away clothed as women. (Roughly half the rebels holding the City Hall were women, so in fact the amount of women's clotyhing was understandable. City Hall was occupied on the ground floor only by the British on the evening of Monday, the final assault was on Tueday morning.)

The official information for that day was that the first objectives for the troops that day were to recover possession of the Magazine in Phoenix Park, where the rebels had set fire to a quantity of ammunition, to relieve the Castle, and to strengthen the guards on Vice-Regal Lodge and other points of importance. The Magazine was quickly re-occupied, but the troops moving on the Castle were held up by the rebels who had occupied surrounding houses, and had barricaded the streets with carts and other material. Between 1.40 p.m. and 2.0 p.m., 50 men of 3rd Royal Irish Rifles, and 130 men of the 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers reached the Castle by the Ship Street entrance. At 4.45 p.m. the first train from the Curragh arrived at Kingsbridge station, and by 5.20 p.m. the whole Cavalry Column, 1,600 strong, under the command of Colonel Portal, had arrived, one train being sent on from Kingsbridge to North Wall by the loop line to reinforce the guard over the docks.

The prisoners were taken to Arbor Hill Prison, and many others, particularly leaders, were escorted to the Castle to be examined by experts. The Rebels had taken possession of the General Post Office and the Telephone Exchange, so that communications were cut off. At Stephens Green the Rebels had taken possession of the buildings of the Royal College of Surgeons, behind which there was Jacobs Biscuit Factory and other buildings which they had fortified, and from which they covered the neighbourhood with continuous rifle fire. Woe betides anyone wearing uniform or any policeman who came within the line of fire, or wandered into the area.

A group of insurgents under the command of Commandant Michael Mallin and his second-in-command Constance Markievicz, established a position in St. Stephen's Green. They confiscated motor vehicles to establish road blocks on the streets that surround the park, and dug defensive positions in the park itself. This approach differed from that of taking up positions in buildings, adopted elsewhere in the city. It proved to have been unwise when elements of the British Army took up positions in the Shelbourne Hotel, at the North East corner of St. Stephen's Green, overlooking the park, from which they could shoot down into the entrenchments. Finding themselves in a weak position, the Volunteers withdrew to the Royal College of Surgeons on the west side of the Green.

At around 7 p.m., I was next ordered to take a small party on a reconnaissance trip round Stephens Green and Grafton Street area. Near Jacobs’s factory the party was recognised and the question arose as to how to get back to the Castle. In front of St Matthias Church I saw a number of men in military formation, and I went back down Harcourt Street, and in front of the Children’s Hospital I noticed a number of rifles in the windows of the upstairs apartments. I was turning over in my mind as to a safe route to take, when suddenly a man walked the hall of a tenement house near Montague Street where we had halted. I covered him with my revolver, got all the information I could out of him, and realising he was of the neighbourhood, asked him if he could guide us back to Dublin Castle. He agreed to do this, and as I knew the streets round well, took him and told him if we were attacked we would shoot him immediately. I placed him in charge of Sergeant Robinson, my platoon sergeant, (Sergeant Robinson appears to have survived the war, as his name is not on CWGC) whom I knew would not hesitate in acting should anything untoward arise. Our prisoner was shaking with fright and could as a result scarcely speak. As I knew in a general way how to get back to the Castle, and warned him with a revolver in my hand, that any move to give us away would be devastation for him. He brought us back through alleys which I was not aware of, and guided us to the back gate of the Castle. I had not much money on me, but I gave it all to him, and told him not to mention the guidance that he had given to anyone

At about 10 p.m. I was summoned to Headquarters at the Castle by military staff. On entering the room the General said that I knew Dublin well, and ordered me to select 12 men and proceed to the Shelbourne Hotel. My job was to clear the front of the hotel of all people and to report if there were Rebels on the premises. With the aid of the manager I entered every bedroom facing the front, and had an embarrassing job, first to request the occupants to leave the rooms, and if they did not willingly comply with my request, to get them out by force if necessary. Being a Bank Holiday, and many visitors having returned from the Curragh Races, needless to say carrying out my job, I came across visitors who were keen on preserving their identity. In doing so there were many who thought it well to quietly comply with orders. At the same time I directed the members of my party to barricade the entrances to the hotel with heavy furniture. My orders having been carried out, I returned alone to the Castle, leaving the men to guard the hotel. I slipped out of the back door of the hotel into Kildare Street where I occupied the attention of snipers. I ran down Kildare Street like a hare and into Molesworth Lane and into Molesworth Street, as a number of rebels were marching along Darwin Street. I got into cover under the front outside wall of the Diocesan School and lay on my tummy for about 20 minutes until the rebels had passed, after which I proceeded back to the Castle without interruption.

Shelbourne Hotel, the machine guns were on the top floor of windows

It was a doubtful advantage to me to know Dublin so well, for after midnight I was ordered to guide a machine gun party to the Shelbourne Hotel. The party was furnished from the Cavalry Brigade which had arrived from the Curragh during the afternoon. It was under the command of a fat major, who was slow in his movements, and as speed was necessary the poor chap was almost exhausted. I am afraid I made the pace too fast for him. We managed to get through to the Shelbourne without any mishaps. We were lucky as Rebel patrols were all around. His job was to prevent rebels from occupying the hotel. I went round with him, and as all the front rooms had already be cleared by me earlier, it was decided to place a machine gun crew in the windows of advantage points, and arranged that the men were not to show themselves, and were to await a whistle signal to fire. The Green was occupied by many Rebels, there were women there, but no exception was made as women had already been found using rifles and taking part in the rebellion. Camp fires and trenches were in the Green. At about 5.30 the signal to fire was given. It was a cheerful but sad sight to see the campers scattering and running out of the far side of the Green.

Officially it was reported that a force of 100 men and 4 machine guns under Capt Carl Elliotson left Dublin Castle at 2.15am on the Tuesday morning and the heavily laden soldiers filtered through the backstreets to Kildare Street, moving slowly to escape detection. They occupied the Shelbourne Hotel at 3.20am, barracaded the lower windows and mounted the machine guns on the 4th floor which gave them a perfect field of fire across St Stephens Green. The troopers then slept till dawn, when they opened fire on the rebels on the Green. The machine guns opening upp was the signal for the storming of the top floor of the City Hall.

At around 6 a.m. I managed to get the RDF men, whom I had left at the Shelbourne earlier in the day, back to the Castle. The College of Surgeons was occupied by the rebels under Madam Markievitz. Later in the day army reinforcements attacked the College, and Madam Markievitz surrendered, walking out in a man’s attire, sword in hand. I remember seeing her, de Valera and Collins with the other rebel leaders, being marched into the Castle Yard under heavy escort. The General Post Office, which was all this time still occupied by the rebels, kept up a heavy fire. Sackville Street, or O’Connell Street as it later became, was one sheet of flame. Liberty Hall, which was the headquarters of the republican unions, had been subject to shell fire from a gunboat in the Liffey, and was surrendered by Thomas Connolly, their leader. Connolly was wounded in the attack and was brought to the Castle Hospital. The rumour got around the Castle that an attempt was to be made to rescue him and the other leaders by attacking the Castle. The result was that guards were doubled and the troops were more or less at “stand too” all night

Tuesday 25th April

Paddy Joe Stephenson inside the Mendicity Institute takes up the tale

...Back again to my post at the window to strain eyes and ears into the darkness of the silent city and wait. Nothing stirred about us and not even a dog barked. ...Some time after daybreak on Tuesday morning, Heuston carried out a thorough inspection of our position....The inspection had made it clear, by revealing our weaknesses that, to put it mildly, our position was not a healthy one...The quays and the street corners were bare and silent now. There were neither soldiers nor highly unintelligent inquisitive civilians about. Nothing stirred. As the morning wore on the only other evidence of the presence of the British in the area was the sound of hammering which came faintly down to us from the Watling Street side of our position, and the barricade at the Watling Street end of Island Street we had observed from the back gate during the early morning. Speculation about the meaning of the hammering occupied us for some time until as it gradually became more distinct its purpose became plain. The British were working along from Watling Street by punching holes through the houses....

.. We saw a number of Volunteers with an officer in uniform at their head turn onto Queen Street Bridge and with a wild burst of cheering rush across it and up Bridgefoot Street. MacLoughlin had come back with reinforcements. They tumbled in over the garden walls of the houses east of us and in front of them came a British soldier minus his arms and equipment. He had been found in one of the back gardens and was made a prisoner. I rushed downstairs to the back door into the courtyard to open it, Liam Derrington who had been posted in a small room beside the entrance to the courtyard was shouting at the top of his voice: "Come down boys, come down, the soldiers are attacking us from the rear". He was getting ready to shoot the Tommy when he saw the rest of our lads come over the walls into the courtyard and held his fire. ...

....That night was quiet and when day broke I went to Heuston and reported there was no food for the increased garrison, except what might have been brought in with the reinforcements...At this point he is sent to the rebel headquarters with a mission, and when he returns the next morning, Mendicity has fallen to the British Army.

Wednesday 26 April

The insurgents had seized buildings on both sides of the Liffey in the vicinity of the Royal Barracks and a group of about twenty men under Sean Heuston occupied the Mendicity Institution on the south side, thus preventing troops moving along the northern quays toward another insurgent stronghold at the Four Courts. The British decided to capture Heuston's position in order to free up their access along the quays. Heuston estimated that he was surrounded by 300 to 400 troops.

Capt Stephen Gwynn, attached to 10th Dublins records that a section of the "inlying piquet" of the 10th Dublin Fusiliers under D O'M Leahy suffered loss when it came under fire from across the Liffy and had to retire.

The British attack began with rifle and machine-gun fire and as combat developed the shooting was frequently at close quarters, sometimes as close as 20 feet. At about noon the British tried a new tactic by sending soldiers creeping along the quay until they reached a wall in front of the Mendicity, from behind which they hurled hand grenades into the building.... Gradually, as one of the defenders later wrote, "The small garrison had reached the end of its endurance. We were weary, without food and short of ammunition. We were hopelessly outnumbered and trapped." As he faced the certainty of being shortly overrun Heuston consulted his men and decided that the condition of the wounded and the safety of his entire garrison necessitated surrender. Although a number of men dissented, the order to that effect was obeyed and the Mendicity became the first rebel garrison of the Easter Rising to capitulate. Irish nationalist revolutionary Heuston was one of fourteen leaders of the uprising to be court-marshalled and executed by firing squad in Kilmainham Jail on May 8tIt appears from evidence at Heustons Court Martial that it was the 10th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers who took the Mendicity Institute.At the Court Martial of Heuston and 3 others the 1st witness was Captain A.W. MacDermot (7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers) who testified that Heuston commanded the party of men who surrendered and that

On 26 April I was present when the Medicity Institution was taken by assault by a party of the 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Twenty-three men surrendered on that occasion. I identify the four prisoners as having been in the body of men who surrendered. They left their arms except their revolvers in the Mendicity Institute when they surrendered. Some of them still wore revolvers. One officer of the 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers (This refers to Lt Neilan's death described above) was killed and 9 men wounded by fire from this Institute on the 24th April. I searched the building when they surrendered. I found several rifles, several thousand rounds of ammunition for both revolvers and rifles. I found 6 or 7 bombs charged and with fuses in them ready for use.

I found the following papers: An order signed by James Connolly, one of the signatories to the Irish Republic Proclamation, directing "Capt. Houston" (Sic) to "Seize the Mendicity at all costs." Also papers detailing men for various duties in the Mendicity Institute. All these papers are headed "Army of the Irish Republic." Also two message books signed by Heuston "Capt." One contains copies of messages sent to "Comdt. General Connolly" giving particulars of the situation in the Institute. The other message book contains copies of messages commencing on the 22nd April two days before the outbreak. One message contains a reference to MacDonagh who is stated to have just left Heuston. Another is a message to "all members of D Coy. 1st Batn." stating that the parade for the 23rd is cancelled and all rumours are to be ignore. Another message dated the 23rd states "I hope we will be able to do better next time."

Capt. MacDermot then testified that Heuston commanded the party of men who surrendered. The 2nd witness was Lieutenant W.P. Connolly (10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers). By November W P Connolly was a Captain in the 10th Battalion when later wounded at the Battle of the Ancre. He stated:-

I was present when 23 men surrendered on the 26th April at the Mendicity Institute. I identify the four prisoners before the court as being amongst them. The leader was J.J. Heuston. I was present when the troops were fired on from the Mendicity Institute on the 24th April, when Lieutenant G.A. Neilan was killed and 6 men wounded to my knowledge. Heuston was without a coat when he surrendered and also had no hat on. He was not in the uniform of the Irish Volunteers. I was present when the building was searched and found arms and ammunition in it and also the documents now before the court. Among the arms there were some old German Mausers. Among the ammunition there were two cardboard boxes of "Spange" German ammunition.

When cross-examined by Sean Heuston, Lieutenant Connolly was not able to say exactly where, in the building, he had found the message books.

By now the rebellion had been put down, and the aftermath was taking is fearful course. My grandfather was involved with the prisoners, censoring mail at the Courts Martial Court at Richmond Barracks. He returned to th 10th Battalion in Royal Barracks about 20th May

During the rebellion, I found many opportunities of nosing into places in Dublin Castle that were normally off limits to all but a very few. I knew some of the history of the Castle to appreciate the opportunities. For example, on a couple of nights, with a few of my troops, we slept in the pews of the Royal Chapel, on the cushions on which some of the highest in the land had sat during divine service. In the chaos that arose during the rebellion, it was a case of seizing any opportunity which would give one a respite.

Leading rebels were examined, and in due course transferred to various prisons to await trial. Many were sentenced to death by Courts Martial. On the cessation of the fighting in the city, after about 6 days, I was posted to the Court Martial Court, which was held in Richmond Barracks. My job was censor to prisoners’ correspondence, which in parts proved interesting and amusing. Some of it contained reference to extramarital family affairs, and affairs of the heart. I saw in the course of my duties all the leaders of the rebellion. During the rebellion I kept a notebook in which I entered interesting instances connected with the rebellion. I thoughtlessly left it on my table, and it disappeared, and although I made enquires, it could not be found.

One afternoon the Chief Officer of the Court Martial summoned me to his room. On entering it, he said we had met before, but at first we could not work out where it might have been. It suddenly occurred to me that I had met him before the war in Dublin and Cambridge playing rugby. We ultimately became friends. The weeks of the rebellion resulted in great destruction in the city of Dublin Throughout Southern Ireland there were spasmodic outbreaks and flying columns of rebels roamed though the countryside.

After about three weeks at the Richmond Barracks I was relieved to my battalion at the Royal Barracks. It was preparing to go overseas. At the end of July 1916 we received orders to embark for England, en route to Pirbright Camp. Fortunately during the interval before leaving the Royal Barracks, I had many opportunities to visit my parents in Rathgar Road. My mother was very ill and I wondered if I would see her later.

A 10th Battalion man, Sergt. J. W. Aldridge, l0th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, was attached to the Royal Irish Rifles in Portobello Barracks during Easter Week. He was witness one of the most bizarre incidents during the rising, and was called at the court martial of the British officer concerned. At 9 A. M. on April 26 he relieved a Sergeant Kelly of the R. I. R. in the guard-room. There were twelve civilian prisoners there, eleven of whom were in the detention-room and one in a cell. The one in the cell he afterwards found was Sheehy-Skeffington. At 10:20 A. M. Captain Bowen-Colthurst, whom Aldridge had never seen in his life before to his knowledge, came in and said he wanted the men named Dickson and Mclntyre and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. They were produced and he ordered them out to the yard. He ordered seven of the guard to come out also. These were all privates, all armed, and each carried 100 rounds of ammunition, while the magazines of their rifles were charged. Witness went out into the yard, and in his presence Captain Bowen-Colthurst told the prisoners to go to the far end of the yard, which they did. He then told the men to load and told them to present and fire. The three prisoners, to Aldridge's belief, were shot dead.

Awards later found in 10th battalion War Diary (Jan 1917)